China’s globalisation paradox.

How can China dominate abroad while becoming less export-dependent?

Factful Friday by Richard Baldwin, 28 November 2025.

Introduction.

China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower, as I pointed out explicitly a while back (Baldwin 2024) and others have confirmed (Garcia-Herrero 2025, Ritchie 2025).

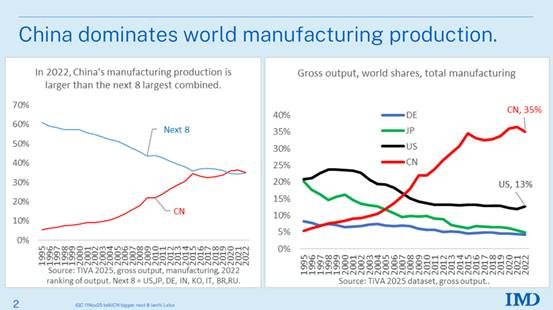

The country produces over a third of the whole world’s manufacturing. Its output exceeds that of the next eight largest producers combined.

Not everyone knows just how dominant China is on the production side. But almost everyone knows how dominant it is on the export side.

But did you know that China has been becoming a more closed economy since the mid-2000s according to standard openness ratios? Did you know that Chinese manufacturing is not particularly dependent on exports?

That’s the China paradox:

· How can it dominate abroad while becoming less dependent on exports?

· How can China be, simultaneously, the world’s factory and less export-dependent than most of the industrialised nations?

That’s the subject of today’s Factful Friday.

The facts.

Look first at China’s dominance of world manufacturing, as the chart below shows (left panel). Today, China produces well over a third of all manufactured goods. That is more than the next eight largest producers combined. The data is from OECD (2023); also see UNIDO (2024).

In comparison, the US, Japan, and Germany are middle powers in the face of the Chinese superpower (right chart). The US world share is about 1/3 of China’s. Japan and Germany are half the US’s world share.

The fact is not shown in the chart, but the reality is that over half of China’s manufacturing output consists of industrial inputs. If you disassemble almost any good bought in almost any nation in the world, it will, almost surely, contain Chinese parts – even if it’s not made in China.

The top exporter too.

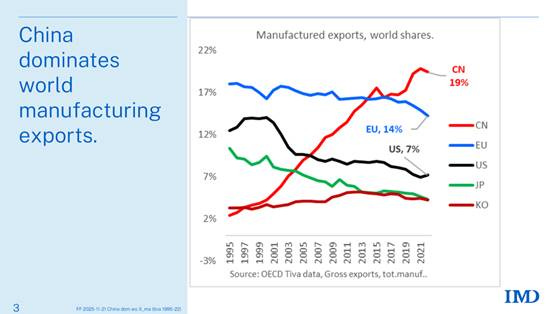

China is also the world’s top exporter of goods, ahead of both the EU and the US. Its share of world exports is huge.

But notice something important in the chart: its dominance in exports is actually a lower extreme than its dominance in production. In other words, China’s factories loom even larger in global production than they do in global trade. It is the world’s factory, but not all of that factory is pointed at foreign markets. That’s the first hint pointing to the paradox resolution.

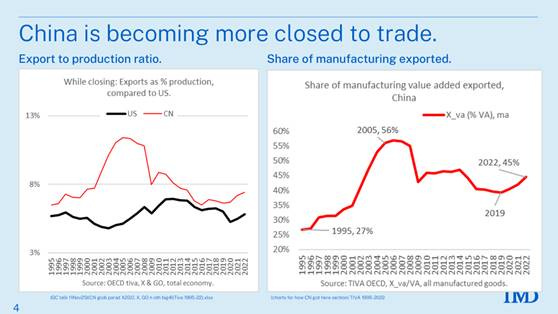

China’s export to output ratios rose but have fallen since 2005.

The openness charts make this even clearer. The share of Chinese manufacturing output that is exported, and the share of manufacturing value added sold abroad, both rose steeply up to the mid-2000s and then started to fall back.

Today those ratios sit much closer to US-style levels (the black line in the left panel) than to the image of an ultra-open export platform.

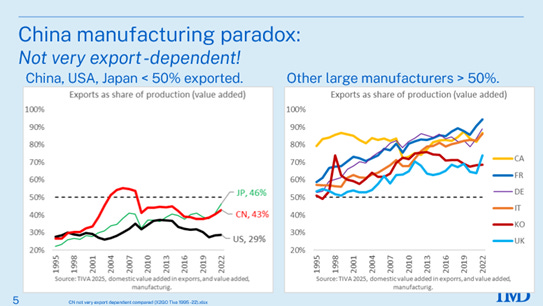

Compared with other big producers, China looks more like a large continental economy – such as the US – that sells a lot at home and a lot abroad, rather than a highly export-dependent economy like Germany or Korea.

Paradox resolved.

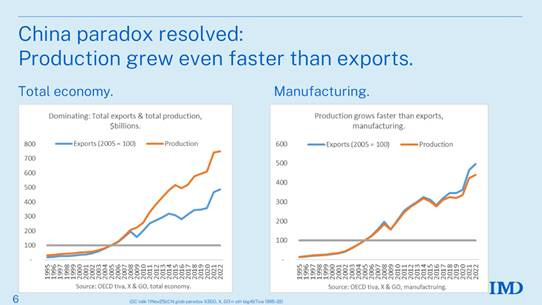

The way to resolve the paradox is to stop looking only at export levels and focus on the race between exports and production.

In the early years of China’s globalisation surge, exports grew faster than manufacturing output. Each year, more and more of what Chinese factories produced was shipped abroad, so openness measures rose. That is the China most people in Washington still have in their heads: an export-led economy whose factories are overwhelmingly pointed at foreign markets.

Since the mid-2000s, however, the race has flipped. Manufacturing output – especially for the domestic market – has been growing even faster than exports. Exports have kept rising in absolute terms and China’s share of world exports has kept increasing, but domestic sales and internal supply chains have grown faster still. When production outruns exports, the share exported must fall. That is all the “closing” really is: not a retreat from the world, but a sign that China’s own market has become so large and dynamic that it absorbs a growing fraction of what its factories produce.

Summary and closing remarks.

China’s globalisation paradox is simple to state. On the one hand, it has become the world’s only manufacturing superpower and the top exporter of manufactured goods. On the other hand, standard openness measures show it exporting a smaller share of its output than in the mid-2000s and depending less on exports than its peers.

The resolution is even simpler to state. If China’s manufactured exports were growing like a bushfire, its manufacturing production was growing like a firestorm. China, you see, is its own best customer for manufacturing output.

China’s exports are rising rapidly – and that’s what most people in the world see. They see world-champion export performance. Chinese export performance wins the gold medal. But what fewer people see is that China’s production performance has, since the mid-2000s, been even more impressive. If there were a medal above gold, then China’s production performance would have won it every year for decades.

This can only mean one thing. A growing share of what China makes is now sold at home rather than abroad.

Closing remarks.

There are important implications of these simple realities.

The facts should reframe your thinking about China’s globalisation experience and its exposure to the world trading system in general, and US imports in particular.

China is still deeply, mutually integrated into global trade, but it is also a vast domestic market that can absorb a great deal of what its factories make. In that sense, we should be thinking of China more like the US: a giant continental economy that trades a lot but is its own best customer. The desperately export dependent China of the early 2000s is no more.

Of course, shutting down Chinese exports would torpedo the Chinese economy, but it would also torpedo the world economy – including the US economy. Supply chains are, after all, golden handcuffs.

That has an important implication for tariff policy. Tariffs on Chinese goods still hurt particular firms, sectors and supply chains, but they do not hit a fragile, export-dependent economy in the way many in Washington seem to imagine. A China that sells a large and growing share of its output at home is less vulnerable to border measures and more able to redirect production towards its own market or to non-US partners.

Trade warriors who are still fighting the old export-led China risk misjudging the economic leverage they have over today’s China.

References.

Baldwin, R. (2024, January 17). China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise. VoxEU. cepr.org.

Garcia-Herrero, A. et al. (2025). “The Chinese economy: stimulus without rebalancing.” Bruegel.

OECD (2023). Guide to OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) Indicators, 2023 edition. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/trade-in-value-added.html

Ritchie, H. (2025). “Trade plays a much smaller role in China’s economy than it did a few decades ago.” Our World in Data, Data Insights.

UNIDO (2024). World Manufacturing Production, Quarterly Industrial Production (QIIP) report, 2024 Q3.

The key point this ignores is the price deflation occurring within China. The type of price deflation China is experiencing indicates that goods AREN'T being sold in China, hence why prices are being cut. And if prices are being cut and profits are declining (which is what the fight against involution is about) then China has some serious problems.

Interesting. I presume a lot of Chinese exports are nowadays effected through third-party countries, like Vietnam. To what extend would it lead to an amendment of the conclusion ?