WTO Rising

Strengthening the multilateral trading system: The ‘WTO rising’ imperative

1 Introduction

The WTO – which was built around yesterday’s consensus to tackle yesterday’s challenges – is being pushed to breaking point by the entrenched disagreements of today. It will need reimagining if it is to rise to the 21st century challenges confronting humanity. And rise it must.

The great trials confronting humanity imperil lives, not just livelihoods. Climate change, the pandemic, and persistent economic inequalities threaten to tear communities apart, spark social upheavals, and foster extremist politics within nations. Between nations, the same factors create strife that may lead to a fractured global economy, to commercial wars, or even real ones.

What does trade and the WTO have to do with this?

Trade is not the only thing we need to tackle these problems, but there will be no solutions without trade. We cannot fight climate change, repair Covid-19’s economic and health damage, or redress economic inequality unless goods, technology, data, expertise, services, and capital move from nations where they are abundant to nations where they are scarce.

This is exactly what trade does. International commerce is driven by arbitrage that moves things from where they are abundant, and thus relatively cheap, to where they are scarce, and thus relatively dear. Much more international commerce will be needed to solve the existential problems. However, the required trade growth will not happen without a high-performing multilateral trade system to provide certainty and to smooth inevitable frictions. This, in turn, requires a WTO that has the status, the clout, and the resources it needs. Call it the ‘WTO rising’ imperative.

This short paper focuses on how the WTO can help with two of the challenges: climate change, and economic recovery from the pandemic. This is not to deny that there is ample room for improvement in other areas of the WTO’s portfolio (see Wolff, 2033, and others).[1]

Before turning to concrete recommendations, we lay out the case that the WTO is simultaneously indispensable and inadequately equipped to handle the scale of difficulties thrown up by climate change and recovery from the pandemic.

2 Buttressing the climate rescue’s trade pillar

Hundreds of millions of people are at risk from climate change, and the disruption, poverty, hunger, disease, and economic and social inequalities it threatens to unleash and exacerbate (IPCC 2021). And the matter is pressing. The IPCC’s 2021 report[2] and the UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report[3] tell us that humanity has only a few decades to rescue itself from the climate change it is causing. The alternative to this climate rescue is human misery on a vast scale.

2.1 Trade is part of the problem but there is also no solution without trade

Solving the problems of too much heat, too little fresh water, and too much seawater (rising seas) all involve know-how moving from nations that have it to nations that don’t. Much of this know-how is moving across borders embedded in goods, services, investments, or intellectual property. This is why any solution that mitigates global emissions without trapping billions in perpetual poverty will require much more trade. As WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala put it in a recent speech: “There is no going green, without going global”.[4]

Taking food for example, a 2021 FAO report points out that food will be much harder to grow in parts of the world where there are many people and easier to grow in places where there are few people. If the billions that are alive today and those to be born by 2050 are to be fed, trade in food must surge, and along with it the movement of agrochemicals, fertilizers, and heat- and drought-resistant variants. Again, that requires more trade.

How, though, will economies pay for the escalation of climate change mitigation efforts and adaptations? Equally critically, how will economies (especially developing and least developed economies) manage the trade-offs between faster and greener growth? Aid, solidarity, and corporate social responsibility programs can be expected to play their part but are unlikely to be enough. The power of the market must be harnessed. Countries importing know-how must generate their own counterflows of goods and services. This will require, economies, most notably advanced economies, to remain open.

None of this is to deny that trade is part of the climate problem. International trade is, after all, woven into the fabric of almost every economic activity on the planet – and most of these activities emit greenhouse gases. Trade is thus inseparable from the climate emergency. However, would curtailing trade make things better or worse?

An analogy might help. Agriculture is responsible for about a fifth of greenhouse gas emissions, but no one argues that we should solve the climate crisis by eliminating agriculture. Starving humanity will not save humanity. The answer with food production – as it is with trade – is to acknowledge that food and trade are simultaneously parts of the problem and integral elements of the solution. They are essential pillars of the economic activity that both support human life and drive climate change.

Frictions are coming – and the system must step up to manage them

Government interventions encouraging more sustainable production, consumption, and growth are positive and desirable, but they will produce trade frictions. Foreign subsidies, for instance, risk causing a domestic backlash if constituencies feel they are being forced to sacrifice disproportionately or are being cheated in the competition for the jobs of the future. Such level-the-playing-field thinking underpins the EU’s proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and it has already caused frictions. A Japanese government spokesman at the June 2021 G7 meeting, for instance, said CBAM sparked “one of the quite controversial, heated discussions among the concerned parties” (Politico 2021).

Without the WTO as a space to share and discuss policies and their resultant frictions, there’s a real risk of nations squabbling while Rome burns. Starkly put, there will be no climate rescue without trade, and managing trade’s role and the inevitable frictions that will arise.

There is no getting around this. The touchstone thesis of the rules-based trade system is that governments set some basic rules of the game, and businesses decide what to make and how based on market signals. Climate mitigation and adaptation however require governments to alter or override market signals in ways that reenforce the fight against climate change.

Put differently, the tools that governments use today to fight climate change, and will increasingly use tomorrow, will unavoidably alter markets in ways that will upset trade partners. As policies such as procurement preferences, production, R&D, and consumption subsidies and taxes increasingly incorporate climate considerations, they will inevitably create winners and losers. The losers will object.

Even if used exclusively in good faith, and innocent of all protectionist intent, policies like border tax adjustments aimed at reducing carbon leakage and/or reducing competitiveness losses, or supply side subsidies designed to encourage domestic production and export of green goods, will still predictably create reactions by trade partners that could easily degenerate into retaliatory cycles. International competition for so-called ‘green jobs,’ while positive, is a likely source of such disputes.

One clear example is that the rush into green industries and the creation of green jobs may create situations akin to what we see in steel. There is every risk of governments subsidising and protecting the same politically attractive green industries while neglecting others, and utilising protectionist measures which limit import competition harm innovation and curtail the dissemination of new technologies.

While binding rules to prevent the frictions above would be desirable, and we envisage and commend the work of negotiators trying to arrive at a consensus toward them, we must be realistic. The odds of the WTO agreeing on such rules are incredibly low, and climate governance is such a new field that any rulemaking today could risk imperilling the policy innovations of tomorrow. Rather, as discussed below, we need mechanisms, procedures, and forums to facilitate transparency and discussion around the policies governments are contemplating and implementing.

Without such a space, there is every risk that governments, operating on imperfect information about the policies of their neighbours and facing political pressure at home, will react in ways that hinder the climate rescue.

3 Reducing poverty and hastening the economic recovery with telemigration

Covid-19 is devastating livelihoods as well as lives. It threw almost 100 million into extreme poverty in 2020 (Mahler 2021). A recovery is underway but moving slowly and unevenly and is now imperilled by economic shocks arising from a polarising conflict in Europe. The multilateral trade system can help reverse the damage by fostering job creation. As ILO Director-General, Guy Ryder phrased it, “Without a deliberate effort to accelerate the creation of decent jobs … the lingering effects of the pandemic could be with us for years in the form of lost human and economic potential, and higher poverty and inequality.”

Creating export jobs is hard but recent developments in international commerce offer hope that the multilateral trade system can boost job creation rapidly. The hope lies in services trade, especially ‘telemigration’ which means international telework (Baldwin 2019). These opportunities are widely underappreciated despite several recent high-profile reports stressing the role of services trade in development (WTO 2019, World Bank 2021, ILO 2021, ADB 2022). Online work also has implications for women’s opportunities since, as ILO (2021) notes: “The preference or need to work from home or for job flexibility is particularly important for women in developing and developed countries alike.”

3.1 Exports of ‘intermediate services’ are booming

Trade in goods has stagnated for a decade, but trade in services has not (Exhibit 3.1). World goods trade grew 4% from 2011 to 2019, but Other Commercial Services (OCS), which basically means office work, rose by 50%, with the growth of travel and transport service exports lying in between. Covid-19 decimated travel and transport, but OCS held up. Goods trade is still the largest component (76%), but services now account for almost a quarter of export earnings globally. As the figures show, two of the three regions hardest hit by the pandemic (Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean) saw goods exports fall in the 2011-18 period but saw service exports boom. Least Developed Countries’ exports experienced slow growth that contrasts sharply with a boom in services (from a small base).

Exhibit 3.1: Export growth in goods and services trade, 2011-2019, and 2019 export shares

Source: WTO Trade in Commercial Services database, stats.wto.org.

Notes: Pandemic disruptions caused travel and transport services to collapse in 2019 and 2020. World goods trade and world services trade amounted to $17.6 trillion and $4.9 trillion, respectively, in 2020.

What sort of services are being exported from, say, Africa? Data from the WTO shows that Africa is experiencing rapid export growth in service sectors that some may not associate with African competitiveness. For instance, between 2011 and 2019, R&D services exports rose by 448% (from a small base), professional and management consulting services by 192%, and financial services by 56%. For complete details, see WTO (2019).

This happened because digital technology opened the door to trade in “intermediate services.” The notion of intermediates is familiar when it comes to goods – intermediates are to produce things while final goods are consumed. Likewise intermediate services are services that go into the production of things, but which don’t get delivered direct to the clients. For example, legal research behind a court filing is an intermediate service, while the court filing is the final service.

Before the ICT revolution made it easy to coordinate complex processes over long distances, most the intermediate services were undertaken a the company producing the final service. Now however, many intermediate services are provided by contract suppliers. The contractors are often domestic, but increasingly they are sitting abroad given the vast wage difference between advanced and emerging markets. This is creating export-linked jobs for bookkeepers, forensic accountants, CV screeners, administrative assistants, online client help staff, graphic designers, copyeditors, personal assistants, travel agents, software engineers, and the like. Calculations using the OECD’s Inter-Country Input-Output matrix show that over half of all existing service-sector exports are intermediate services rather than final services (authors’ calculations).

An important point is that intermediate services face few barriers because existing service-sector regulations overwhelmingly target final services only (OECD 2022).

3.2 Service-export-linked jobs are booming

Service exports tend to be “job-rich” since services tend to be labour intensive. This point can be seen in OECD data that uses Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) analysis to calculate the number of jobs associated with trade in all sectors, including service sectors. The data only cover OECD members and a few large non-members, but they are revealing.

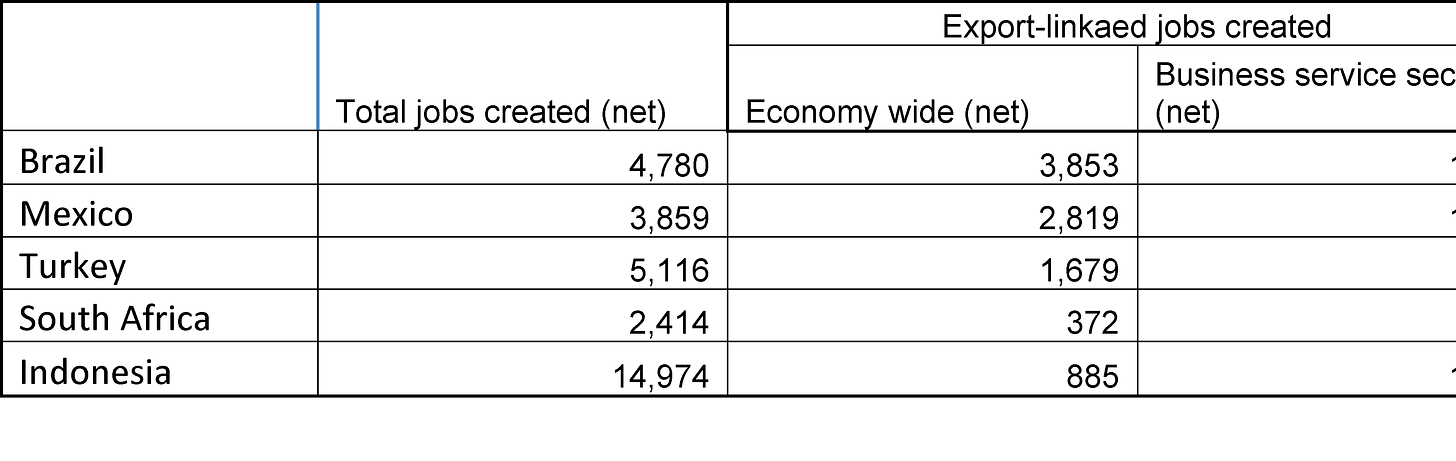

Exhibit 3.2: Importance of business service exports in overall job creation, 2011 to 2018 (1000s)

Source: OECD Employment in Trade dataset, 2021 edition. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TIM_2021

For a selection of nations, Exhibit 3.2 shows the number of jobs created in the country overall (first column), and those related to exports in second and third columns. In Mexico and Brazil business service jobs linked to exports were a big slice of the total, economy-wide job creation. In Turkey, the figure, about 15%, was smaller, but new Turkish jobs that were linked to business services were a third of all new export-linked jobs. In South Africa, service exports accounted for a high share of all export-linked job creation, about 90%. For Indonesia, export-linked business-service job creation was much lower share of all job creation, but since non-service export jobs actually fell in the country, the service-export-linked job creation, equal to 1.357 million, was more than 100% of export-job creation in all sectors.

The point is that services exports are already an important source of export jobs. The expansion is widespread and includes least developed nations which were hit so hard by Covid-19. This is why we believe that supporting intermediate services exports is one vital way for G20 leaders to foster economic recovery from the pandemic and reverse the rise in poverty.

Critically from a poverty reduction point of view, the jobs in services export sectors are providing opportunities to segments of the population that do not historically benefit as strongly from manufacturing led growth, as well as to SMEs which might otherwise struggle to harness the capital, global reach or economies of scale to compete internationally in goods. There is an inclusivity dividend to be collected, if governments work hard enough.

4 Specific policy recommendations

Ensuring that trade helps rather than hinders the climate rescue and helps speed the recovery with service-export-linked jobs are two very concrete challenges that G20 leaders can address this year. We start with trade’s contribution to the climate rescue.

4.1 Building the trade pillar of the climate rescue

The first specific recommendation on climate is premised on three realities: 1) There will be no climate rescue without a well-functioning world trade system. 2) The trade system will come under enormous stress since national climate plans involve policies – like subsidies, border taxes, and preferential government procurement – that will inevitably create trade clashes. 3) To keep the climate rescue on track, G20 leaders must prevent the conflicts from derailing adoption of national climate policies.

Recommendation #1: There is nothing new about the disputes that will arise, but disputes over policies motivated by concern for humanity’s future should be treated differently from ordinary commercial disputes. G20 leaders should create a process, together with the WTO leadership, that prepares the ground for climate-related disputes, and ultimately leads to a new infrastructure for handling climate-related disputes via mediation, negotiation, discussion, and adjudication (a restored or re-imagined binding dispute settlement mechanism would be an optimal outcome even if it is unlikely in the short term).

The new process should start with scientific, economic, legal, and political fact-finding and analysis. The process should be open, transparent, and inclusive. We stress that it must include scientific expertise since the efficacy of climate policies will surely matter in the disputes, and rapid technological advances are continually changing the meaning of ‘least trade distorting’ policies. Given its existing expertise and near-universal membership, the WTO should be provided with the necessary resources and mandate to evolve and take on this new role.

This new system need not be a revolution. The WTO of today does have mechanisms for addressing these frictions but they are limited, siloed, and do not systematically recognize the climate imperative. We propose the establishment of holistic, and sustainability-centric procedures and guidelines. The new infrastructure should enable the WTO and its strengthened and empowered Secretariat to rise up as a facilitator and illuminator of these climate-related disagreements, and a fair-broker providing good offices where day-to-day tensions can be aired, discussed, moderated, and resolved.

As part of this, G20 leaders should stress the usefulness of the Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD) that are already ongoing at the WTO. These discussions, which are typical of the new WTO approach that allows like-minded members to cooperate under the WTO umbrella, are not a replacement for the mandated Committee on Trade and Environment, they are a supplement. The key point is that like-minded nations will cooperate somewhere. It might as well be in the WTO since it has a long tradition of openness and inclusion. There is no ‘Security Council’ or ‘Executive Board’ in the WTO.

TESSD meetings, open to any WTO member whether they are a signatory or not, represent the most established and active venue to host discussions between all WTO members about the types of policies they’re contemplating, how these will impact other members, and how emerging frictions can be managed. Importantly and unusually, TESSD is also open to stakeholders other than governments, lending its deliberations an inclusivity vital to maintaining public support and ensuring maximal, broad input.

G20 policymakers have an opportunity to demonstrate leadership around this initiative by agreeing to participate actively in TESSD discussions and supporting the WTO Secretariat in fully resourcing and supporting them. Critically, participation in the discussions and deliberations of the TESSD need not entail a commitment to participate in any evolution of the TESSD’s discussions toward plurilateral rulemaking, which some G20 Members consider inappropriate.

More broadly, G20 policymakers should recommit their officials and ministries to fully embracing the monitoring, deliberation, and transparency pillars of the WTO, especially on climate related issues. Though not as headline- grabbing as negotiations or disputes, the WTO’s role in shining a light on policies and allowing their implications to be discussed may prove even more critical to preventing the climate rescue descending into green trade wars.

Link the trade and climate communities

The climate and trade communities are siloed and separated. This cannot continue. The WTO should be explicitly included in efforts to advance, amplify, and coordinate the climate rescue. Thus:

Recommendation #2: G20 leaders should call for the creation of a meeting co-chaired by the WTO Director-General and the UNFCCC Executive Secretary or COP Presidency on the program of each COP meeting. The meeting would have as it goal the coordination of international efforts on trade and climate. A signal, from the very top, that trade policy is an ally of the climate fight, and that climate is an indispensable consideration for trade policy is imperative. The G20, and then the WTO and COP in partnership, can provide that signal.

4.2 Facilitating the economic recovery with service export jobs

Emerging and developing country service exports have boomed with little or no international cooperation. India’s services export miracle, for instance, was accomplished without a single trade agreement being signed. We believe service exports, and the creation of associated jobs, will continue to thrive given the lack of formal barriers to trade in intermediate services and the explosive pace at which digitech is making remote workers seem less remote. There are, nevertheless, some steps that G20 leaders should take to prevent new roadblocks being placed on this new pathway to prosperity.

In the medium run, the rapid growth of telemigration will change the lives of office workers and professionals and create upheaval in advanced economies just as the rapid rise of manufactured exports did during the last decades (Baldwin 2019). The upheaval is then very likely to produce new forms of protection to limit telemigration that will look quite different to protection in goods sectors. It is not feasible to put Trump tariffs on, say, American companies having telemigrants check receipts against expense claims. One possible backlash may be to use privacy and national security regulations to hinder the necessary cross-border information flows.

Recommendation #3: To manage future backlash, G20 leaders should establish an eminent persons’ group to think ahead about how the WTO can anticipate and monitor the backlash as well as suggesting updates to the rules-based multilateral trading system necessary to accommodate the rapid rise of services trade as well as rethinking the trade-development nexus and the WTO’s role.

As with the 1958 Haberler Report, the committee should prognosticate how the world trade system can address these barriers in a fair, transparent, and inclusive fashion.[5] Part of the mandate should be to develop significantly improved ways of measuring services trade, and of identifying barriers to trade in intermediate services. Today, the measurement of telemigration is abysmal since statistics on trade in services have not received the attention and resources that they deserve in the 21st century. The WTO should be given the resources to investigate ways of setting up development-friendly statistics gathering, potentially through new or expanded partnerships with others like the IMF.

5 Concluding remarks: The ‘WTO rising’ imperative

The measures we call for in this paper are not dramatic. We do not suggest that G20 leaders call for a grand new update to the WTO rules, a treaty-based, unified global carbon price, or a restoration of the WTO Appellate Body. While laudable goals, the likelihood of securing a consensus on these changes in the time we have is low. However, there are still practical steps to be taken.

G20 leaders can provide the WTO with an infusion of the political capital and focus it needs to rise and evolve to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Perhaps even more critically, by focusing on the monitoring pillar and enhancing the WTO’s function as a transparency and discussion forum, G20 leaders can give the organization new life without first solving longstanding areas of contention.

More broadly, to ensure international commerce plays its role in tackling humanity’s existential challenges, the status and clout of the WTO must rise. International commerce will be one of the economic mainstays in the fight against climate change and extreme poverty, and the global effort to reduce inequality via the creation of export-linked jobs in developing and emerging economies. The WTO rising imperative is about increasing the likelihood that international commerce remains as rules based as possible while supporting sustainable, inclusive, and equitable growth.

Above all, a mindset change is needed. Leaders must recognise that the WTO is not just about commercial calculations best left to diplomats and trade ministers. It is about coming together to find ways of countering the challenges that endanger humanity. It is about saving millions of lives. It is about countering developments that threaten to lock billions into perpetual poverty. It is a place that requires head-of-state attention and the status to match. We are arguing that G20 leaders need to perceive trade as part of the solutions to humanity’s existential challenges, and ‘WTO rising’ as an imperative.

References

ADB (2022). Asian Economic Integration Report 2022: Advancing Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific, ADB, Manilla.

Baldwin, Richard, and Rikard Forslid (2020). Globotics and development: When manufacturing is jobless and services are tradable. NBER Working Paper 26731, Cambridge MA. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26731/w26731.pdf

Baldwin, Richard. The globotics upheaval: Globalisation, robotics, and the future of work. Oxford University Press, (2019).

Benz, S. (2017), "Services trade costs: Tariff equivalents of services trade restrictions using gravity estimation", OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 200, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dc607ce6-en.

FAO (2021). 2021 (Interim) Global Update Report: Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in the Nationally Determined Contributions, FAO, Rome.

Gao, Henry S (2021). “WTO reform and China, Harvard International Law Journal.

Hopewell, Kristen (2021). “Trump & Trade: The Crisis in the Multilateral Trading System”, New Political Economy, 2021, vol. 26, issue 2, 271-282.

ILO (2021). Berg, J., Hilal, A., El, S. and Horne, R., 2021. World employment and social outlook: Trends 2021. International Labour Organization.

ILO (2021). World Employment and Social Outlook 2021: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work, ILO, Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2021/lang--en/index.htm

IPCC, 2021. “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis”, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C.

Mahler, Daniel et al (2021). “Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: Turning the corner on the pandemic in 2021?” World Bank Blogs, 24 June 2021.

Neufeldt, H., Christiansen, L. and Dale, T.W., 2021. Adaptation Gap Report 2021-The Gathering Storm: Adapting to climate change in a post-pandemic world.

OECD (2020). OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy trends up to 2020, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2022). OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy Trends up to 2022, OECD, Paris.

Politico (2021). “The EU’s carbon club of one: Brussels seeks G7 support as it pushes ahead with a border tax for carbon, but the US and Japan are concerned,” https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-carbon-border-tax-support-g7-us-japan/

Srinivasan, T. N. (2020). Developing countries and the multilateral trading system: from GATT to the Uruguay Round and the future, Routledge, ISBN 9780367009892.

Wolff, Alan (2023). World Trade Governance; The Future of the Multilateral Trading System, Cambridge University Press.

World Bank (2021). “At Your Service? The Promise of Services-Led Development”, Nayyar, Gaurav; Hallward-Driemeier, Mary; Davies, Elwyn. World Bank, Washington https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35599

WTO (2019). World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade, WTO Secretariat, Geneva.

[1] A preview of Wolff (2023) is available at https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/wto-2025-restoring-binding-dispute-settlement. Also see Srinivasan (2020), Gao (2021), and Hopewell (2021), inter alia.

[2] AR6 Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (Sixth Assessment Report)

[3] UNEP 2021 Adaptation Gap Report: The Gathering Storm

[4] Delivered (remoting) 8 April 2022 to the NBER Trade and Trade Policy Conference, Cambridge MA.

[5] A report by a panel four eminent experts commissioned to forecast trade trends and provide suggestions for the GATT contracting parties ahead of their 13th Session in Geneva on 16 October 1958.