Why is America acting this way on trade?

A globotics shock, a failed social policy, and middle-class fury.

Posted on LinkedIn: March 30, 2025; Reposted on Substack: 4 August 2025.

Richard Baldwin, Professor of International Economics @IMD , 30 March 2025, Factful Friday.

Introduction.

US trade policy has gone rogue, puzzling traditional allies and foes alike. What happened to the architect of the rules-based trade system—the one-time champion of open markets and predictability in trade? Tariffs, hostility to multilateral institutions, and constant brinkmanship have become the norm.

Like the parents of energetic teenagers, people around the world are asking themselves: Why are they acting this way? Is it something we did?

It’s hard to make sense of US trade policy in any case, but it is nigh on impossible unless you understand the discontent of the American middle class and how it has built up over decades under Democrats and Republicans alike.

Since Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the US systematically dismantled the New Deal-era safety nets to finance tax cuts, thus eroding the security of ordinary Americans. Then came the twin forces of globalisation and automation—the “globotics” shock—which dramatically deepened inequality. While skilled knowledge workers thrived, the livelihoods of manual and middle-skilled workers crumbled. Unlike other advanced economies, there was no social policy to smooth over the globotics upheaval in the US. Middle-class Americans faced displacement alone, fuelling anger and frustration with traditional Democrats and Republicans. Eventually, the anger led to a political backlash that brought to power a populist with protectionist instincts (twice).

The key point of today’s Factful Friday is simple. It is tempting to treat Trump’s tariffs and threats as the cause of a new era in US trade relations. But in truth, the sharp break masks a long accumulation of discontent. Policies that would actually help the middle class—the sharing and caring policies that workers enjoy in every other advanced economy—would make sense, but they are entirely off the American political radar screen. Since the real solutions cannot be rolled out, and something must be done, protectionism is the natural result.

This is why we shouldn’t think of the US as putting up tariffs as part of a solution; they are being raised as an excuse for not undertaking policies that would actually help alleviate middle-class malaise. Tariffs are also attractive politically since they come with the side benefit of making Americans think that the middle class’s problems are not “Made in USA”, they are “made by foreigners.”

Why is America's middle class so angry?

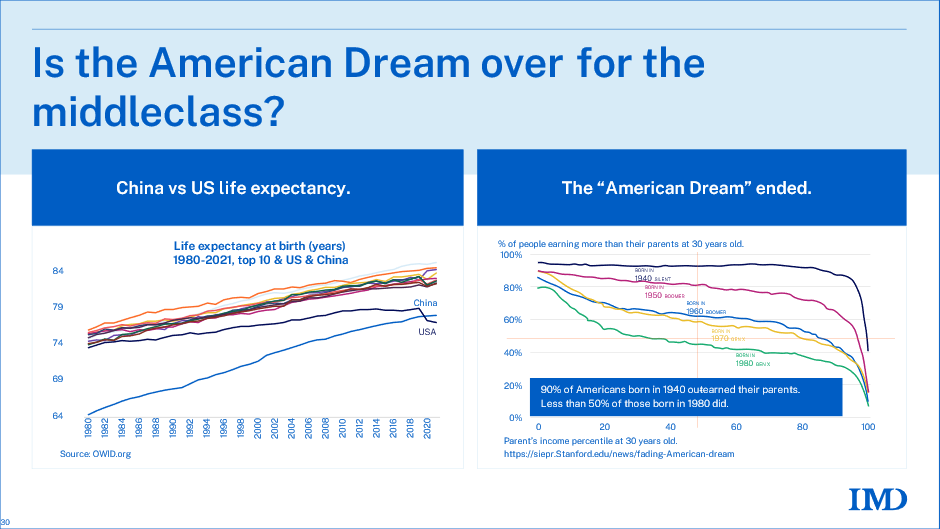

The anger simmering in America’s middle class isn’t irrational—it’s economic reality. Many Americans cannot even dream of buying the home they grew up in. There is no way they’ll have the job security that their parents took for granted. They are finding it hard to afford a middle-class living on today’s middle-class incomes.

But it is not just about the prices they pay and how much is in their wallets. Pride matters. The last few decades have wounded the pride and shaken the confidence of many working Americans for whom the American Dream was disrupted—especially those who didn’t go to university, but even many who did. Here is a link to a whole slew of Pew Research charts demonstrating the socio-economic woes of the US middle class. They illustrate how the American Dream wasn't always an empty slogan.

From Helping Hand to Trickle Down.

The American Dream is not a promise that you’ll do well. It is a belief. It is a hope. It’s the idea that working hard, showing up every day and giving it your best will allow anyone—regardless of background—to build a better life for their families. Part of the Dream was a belief that regardless of the nature of the shocks and shifts, you’d have a fighting chance of being one of the winners.

This belief was underpinned by Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies. With FDR’s New Deal, the role of the government was to help the little guy—to look after economic stability, full employment, and basic welfare. To fight cartels and break up monopolies. That’s when Social Security and unemployment insurance were invented. Unions and collective bargaining were legalised, protected, and encouraged. The Fair Labor Standards Act put a floor on workplace conditions.

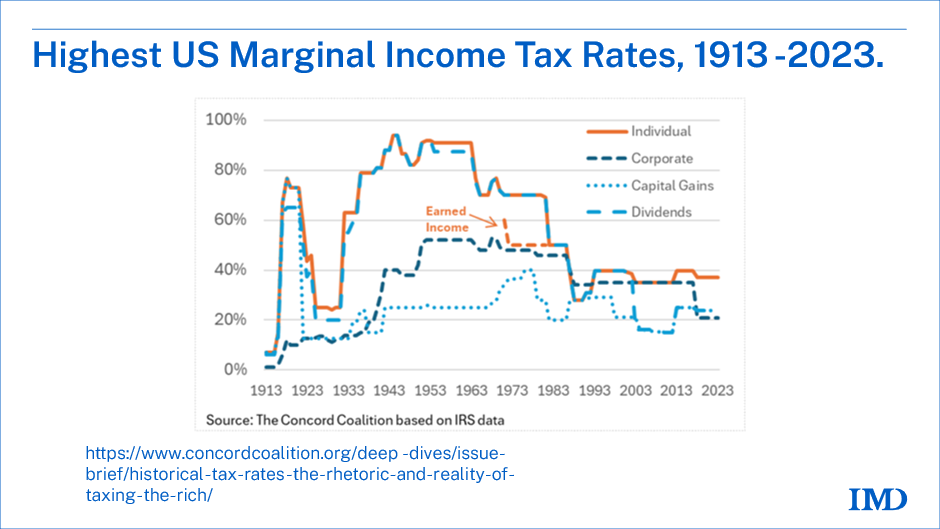

Then came Reaganomics. From the 1980s, the US pivoted from Franklin D. Roosevelt's vision of government as protector to Ronald Reagan’s supply-side economics and the trickle-down theory. When Reagan took office in 1981, the top marginal income tax rate was about 70%. Ten years later, it was down to about 40%. This is where it has stayed for the last 35 years, unchanged by Democrats or Republicans.

These tax cuts weren't free—they were paid for by eroding America’s social policies. The government didn’t eliminate all social policies since many were too popular to kill. But the visible helping-hand of the government was steadily replaced by the invisible hand of the market—undermining the safety net that working families used to be able to count on in hard times.

Globotics Shock: Globalisation Meets Automation.

This weakening of social policy coincided with another seismic shift: the ICT revolution, which accelerated industrial automation from the 1970s and turbocharged globalisation from the late 1980s. The economic impact of this combined shock—what I call the globotics shock—caused massive labour force dislocation in all advanced economies.

ICT advances offered better substitutes for manual labor, depressing wages and job opportunities for middle-class workers. At the same time, ICT created better tools and raised the productivity of highly educated workers. Both changes fuelled a sharp rise in inequality in the US, and middle-class resentment.

Exceptional Vulnerability of the American Middle Class.

While the globotics shock hit every advanced economy hard, the removal of FDR style social policies left America uniquely unprepared for the economic disruption. Unlike Canada or European nations, the US lacked universal healthcare, strong unemployment benefits, paid parental leave, affordable higher education, and effective retraining programs. That is why the American middle class had to face the globotics shock and resulting economic upheaval without the social policy adjustment mechanisms that soften the blow in all other advanced nations.

The result devastated the middle class leading to outcomes never seen before: frequent school shootings, an opioid crisis, an obesity epidemic, medical bankruptcies, high maternal mortality rates, crushing student debt, world-leading incarceration rates, high rates of old-age poverty, concerning levels of homelessness, rising suicide rates among white middle class people, and other deaths of despair. Such social pathologies are unknown at comparable levels in other advanced economies.

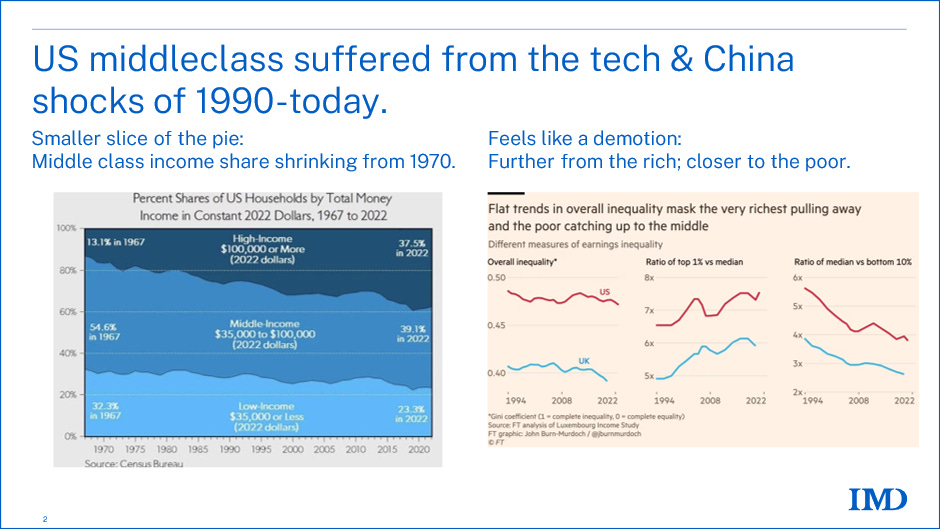

All the while, the middle class was forced to witness the rich pulling away from them on the upscale side, while the poor were catching up on the downscale side—as John Burn-Murdoch showed in his recent Data Points column.

If you think about that, you’ll see that the American Dream is working—just not for the middle class.

In short, the slow-burn hardship confronting the American middle-class for decades is not a result of technology and globalisation shocks. Nor is it the middle-class’ fault. It’s a result, in my view, of the shocks hitting a society that had removed the FDR social policies that had been left in place in all other advanced economies. It was the shocks without a safety net, not the shocks alone.

Political Backlash.

It’s hardly surprising that the middle class grew angry—deeply, justifiably angry. Every four years, they elected a traditional Democrat or a traditional Republican, but none of them provided meaningful relief. They didn’t even provide credible plans for fixing America’s socio-economic problems. The sticking point, you’ll understand, was that creating the necessary social policies would have required higher taxes—a policy that had become politically impossible in the US, for reasons that are hard to pinpoint.

These facts, in my reading of history, ultimately contributed to the election of a billionaire who blamed globalisation and wokeness for the middle-class devastation. This billionaire has promised to help the middle class by pulling away even more social policies. He is shrinking the social safety net, and—wait for it—cutting taxes for corporations and the well-to-do. It’s hard to see this as a winning sales pitch to the US middle class, but it worked.

My explanation is that in their anger at traditional Democrats and Republicans for having failed them for decades led them to try something, anything, that wasn’t more of the same. After decades of disappointment, something had to change. Come the hour, come the hero, as they say. Or at least that is one way to comprehend the political earthquake that happened in November 2016 and 2024.

Why the anti-trade emphasis?

While the backlash and election of a populist is understandable given the length of the fail-trail traditional politicians have left behind themselves, the question remains: Why is today’s populist so anti-trade? In part the answer is: Why not?

Populism is a shallow political philosophy. The touchstone is a simple mantra: The people are pure; the elite are corrupt, so elect me and I promise to (this space is left blank on purpose).

Any policy suits as long as it can be portrayed as something the elite has not been doing—especially if the fill-in-the-blank policy would outrage the elite. The point is that populism is driven by anger—not a careful study of what made the people angry, or what policies would address their plight. At various times in living memory and in various countries, the fill-in-the-blank policy ranged from far left to far right: from fascism, communism and the Cultural Revolution to Brexit and extreme anti-immigration promises.

Tariffs as Trump’s hobgoblin.

The real source of the anti-trade bias is a deeply held conviction of the leader of the populist camp. Donald Trump is not a man troubled by the hobgoblin that Ralph Waldo Emerson was referring to when he said: “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” He has been pro- and anti-gun control, pro- and anti-choice, pro- and anti-Hillary Clinton, and he has even been both a Democrat and a Republican. But the one hobgoblin he has held on to all along is the near-magical promise of tariffs.

In the 1980s, as a private businessman, Trump took out full-page advertisements in major newspapers to criticise US tariff liberalisation. In the ads, you can see how even back when America was great—as in Make America Great Again—he believed that the US was being treated unfairly in international trade.

While tariffs and anti-globalisation fulfil all the requirements for a fill-in-the-blank populist policy in today’s America, this policy has one really big problem for the populist in chief.

• Tariffs won’t fix the plight of the American middle-class.

Tariffs can raise the price of goods that are made domestically, and this can in principle help the firms and workers making those goods. That’s textbook economics.

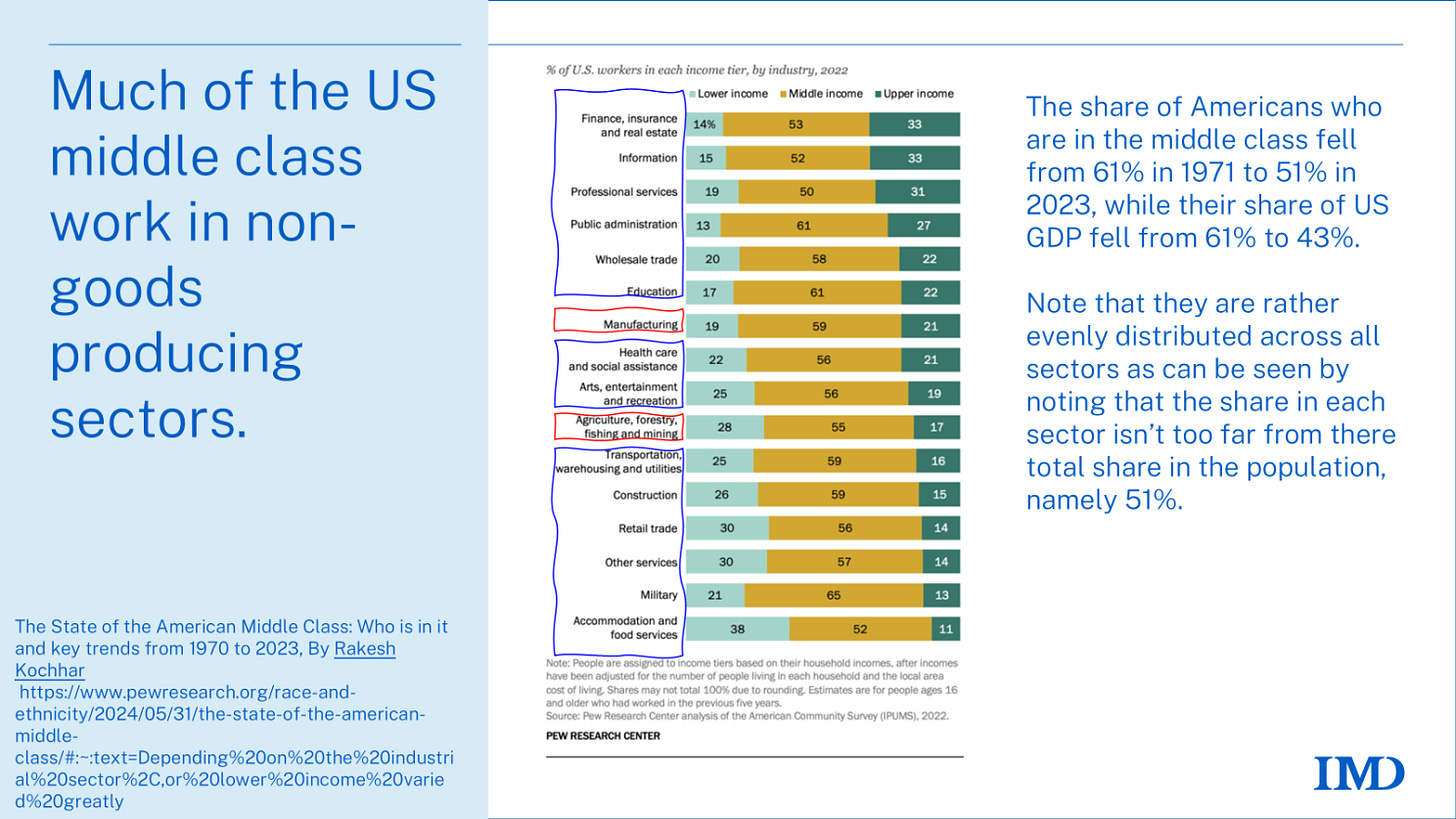

• The fly in Trump’s ointment is that the US middle class do not, for the most part, work in goods-producing sectors.

Those sectors are really quite small. Counting all workers, only about 8% of the US labour force have jobs in manufacturing, with only another 2% in agriculture, mining, forestry, fishing and the like. The chart shows that the US middle class mostly have jobs in service-producing sectors—not goods-producing sectors.

The key point here—the reason tariffs won’t help US middle-class malaise—is that tariffs don’t defend workers in service sectors, just the opposite.

• Tariffs get put on goods when they go through customs. Since services don’t go through customs, they can’t be tariffed.

But tariffs are worse than just not being helpful to the middle class. Tariffs raise the prices of goods that the whole middle class has to buy.

• Tariffs will lower the real wages of the people who were so angry about rising prices in 2024.

I’m waiting to see how they will react when they see that tariffs have driven up the prices of things they buy every week in Walmart.

Wisdom of the ages: if you can’t fix it, find a scapegoat.

So tariffs won’t help the middle class. At the same time, the solutions used in other advanced economies to help the middle class won’t work since the US median voter is miles away from believing that more government and higher taxes would improve the situation.

Given there is no solution that is both economically effective and politically feasible, the American political classes—Democrats and Republicans alike—have turned to the time-honoured Plan B—convince the voters that it is someone else’s fault. When they realise that they can’t fix a problem, any politician will tell you that the next thing to do is to find someone else to blame. The full spectrum of the US policymaking community has decided that foreigners and trade in goods are an excellent candidate for the role of blame-eater—China in particular.

Tariffs, to my way of thinking, aren’t popular with US politicians because they are a tried-and-true solution for middle class malaise. Tariffs are popular with them because they are a substitute for politically unpopular policies that would work. And tariffs come with the side benefit of making it seem like the middle class’s problems were made abroad.

Summary and Concluding Remarks.

To sum up, America is acting this way on trade for three reasons.

The first, the root cause, is deep, lingering, rage-inducing adversity faced by the US middle class.

The second is that policy that might actually help them overcome the adversity are entirely off the American political radar screen. Canadian-style social policy would go a long way to lifting up the left behind, but for reasons that are hard to pin down, that is the “third rail” of American politics—touch it and you die instantly.

Third, America’s strong-willed leader believes, on the one hand, that tariffs have near-magical effects, and, on the other hand, that America is being ripped off by trade since America buys more goods than it sells.

So far, the magical thinking has not come up against reality. Not that many tariffs have actually been imposed and in any case, the price rises usually are not instantaneous. Moreover, the US president seems to be working in a closed, wishful-thinking bubble that his advisors dare not burst. In my view, this has led to incredibly erratic trade policy, which strikes most of the world as just bizarre (as well as frightening).

Closing remarks.

It is tempting to treat Trump’s tariffs and threats as the cause of a new era in US trade relations. But in truth, they are a symptom. The sharp break in tone masks a long accumulation of discontent. If Trump’s trade policy is the earthquake, the middle-class malaise is the tectonic shift that made it inevitable.

Information and Communication Technology joined forces with and amplified globalisation in a way that created better substitutes for many middle-class workers but better tools for high education workers. This shock hit the whole world. In the Advanced Economies it fostered de-industrialisation, income inequality, and socio-economic dislocation. Given its failed social policies, these common shocks had uniquely pernicious effects in the US. They formed a fertile social and political soil in which the new trade populism sprouted and thrived.

In short, US trade policy is not being used as a solution, it’s being used as an excuse for not undertaking policies that would actually help alleviate middle class malaise. It may also be being used as camouflage for deep domestic power shifts, but that’s a topic for future Factful Friday.

I do not agree with most of this. I received my PhD and wrote on trade theory in 1977. I was in France in 1971 when Nixon closed the gold window...ouch.

I did the trade and current account forecasting at the NY Fed starting when Paul Volcker was president there. I was chief of the international financial markets division in the NY Fed and subsequently chief economist at NIkko Securities (US). I have traveled and worked internationally. and wrote under Max Kreinin, a well-known free trade enthusiast. So..I am no outsider to this. here is what I think... you need to answer -at least to convince me.

Why does the US have 33 straight years of current account deficits?

Why don't exchange rates move to eliminate or reduce the deficits, a theory USED TO teach?

US current account deficits, if they were a country, would be the 17th or so largest county in the world by GDP. US would be about 7th largest country by GDP. Why does the US import so much and export so little?

Isn't trade theory about more than cheap imports?

Isn't it true that if the dollar was supposed to adjust to reduce a current account deficit> to remedy the US deficit it would fall and import prices would rise! Doesn;t moving import prices higher align them more with a true free trade result at a time that exchange rates are dysfunctional?

Isn't trade supposed to be mutually beneficial?

Where is our export benefit?

Is this a Triffen problem? You know what that means...

Or is it some other reserve currency issue? I think countries use the US reserve currency story <as an excuse> to run their macroeconomic policies through their exchange rate to generate growth off of US imports <US Demand>.

This is NOT free trade- it is freeloading.

in robert Solow growth models there is a focus on intergenerational fairness in that mode. I-dot = S-dot <the time derivative of investment equals savings> . What about in trade? today's deficits ('fund' imports and substantially consumer goods and raw materials—benefits today's consumers, and IOUs are rung up to be paid by future generations—is that fair?

You say most workers are in service? Well, yeah! That's the problem! We are priced out of the goods sector < and yes, technology has also played a key role in reducing employment demands in the goods sector> .But is that a reason to give up?

I grew up in the Michigan Detroit area and suburbs. I worked on the assembly line and could make enough $$ in the summer to pay for college the next YEAR. Those days AND JOBS are gone.

Do we let currency manipulators run the show and determine what we can do?

This is not, and it has not been, free trade.

The theory of second best TEACHES us not to pursue 'first best' policy options if we are in a second best world because they will not lead to optimization. I'd say Trump has learned that lesson.

Have you?

Respectfully,

Robert Brusca, PhD

Economist, NYC

Very happy that your posts have arrived on Substack! Would love to read more about concrete policies to help the middle class!