Is China misthinking manufacturing?

China’s problem isn’t just overproduction in manufacturing, it’s also underproduction of advanced services.

Richard Baldwin, 26 December 2025, repost of 17 May 2024 Factful Friday with some updates.

Introduction.

The whole world is going crazy over manufacturing. Nations are splashing around industrial subsidies like champagne at a Monaco Grand Prix victory. And they are throwing up tariff barriers to prevent foreign teams from enjoying the bubbly.

China is where this “manufacturing mania” is perhaps the most apparent. For decades, it’s been the national mission. Local government officials, guided by central government dictates, have competed among themselves for glory and promotion by stimulating local industry (Li 2024, Chapters 3 and 5). They attracted manufacturing by offering free land, cheap loans, energy, and infrastructure, as well as fiscal incentives (Wang 2023, Chapters 4 and 5).

It has been called the “mayor economy” (Jin 2023) because the mayor of each locale (a communist party official) fosters manufacturing facilities. Success and subsidies were more or less guaranteed as a kind of race-to-the-bottom played out among mayors (Li 2024, Chapters 7 and 8).

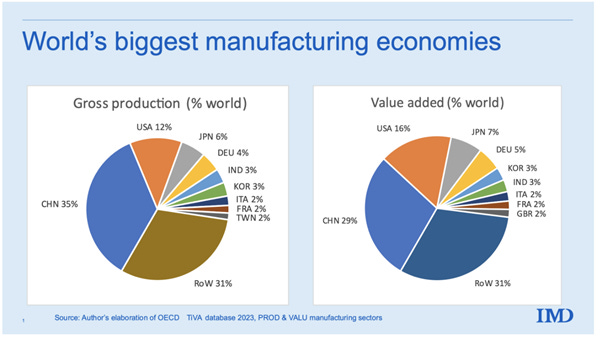

I’m no China expert, but from my readings, “It’s the Mayors what done it,” as Shadwell said in Good Omens (Li 2024, and Gaiman and Pratchett, 1990). That’s how China’s manufacturing output soared from about 5% of the world’s in 1995 to 35% in 2020, as I showed in Baldwin 2024. Trouble with this economic model is that the mayors know how to do industry and infrastructure. They have never shown competency at incentivising domestic consumption without digging or building something. But why the focus on manufacturing?

It is simplicity itself to understand why China prioritized manufacturing for the past 25 years. That’s how all their role models did it. What worked for today’s rich countries in the 1800s, for the USSR in the 1920s, and for Japan and Korea post WWII, will surely continue working for China in the 2020s, n’est-ce pas?

What that great economic historians have to say.

Gordon (2016) argues that the manufacturing-led growth in the West was the core of a “special century” that was historically unique; unlikely to be repeated. The subsequent shift toward services was, in his view, a natural consequence of successful industrialisation, reflecting high income levels, changing consumption patterns, and diminishing returns to further manufacturing-based transformation.

For Joel Mokyr, who got the Nobel Prize this year, rapid industrialisation was also a singular historical episode, but he rejects Gordon’s view that there is something special about manufacturing and technological progress (Mokyr 1990, 2009). He rejects Gordonian technological exhaustion hypothesis, asserting instead that knowledge-driven innovation is open ended. Future growth can arise in knowledge- and technology-intensive services such as health, education, research, and digital activities (Mokyr 2014, 2018). In short, the great western economic historians say: rapid industrialisation? Yeah, that was great but it’s a story that’s run out of runway. To reach high-income status, economies must move into services.

But why listen to economists when you can fall back on what you learned in high school history class? Nations around the world are convinced that industrialisation is the key to growth. Leaders ranging from President Biden of the US and President Macron of France to President Xi of China and Prime Minister Modi of India act as if one would have to be a Troglodyte to believe otherwise. One example is Modi’s “Make in India” push when the nation is a world-beater in service exports. (See my 15 March 2024 Factful Friday on this.)

I’ll have more to say about the historical sources of such beliefs in the sequel, but let’s first look at the facts.

· Is it really Troglodytic to question the importance of manufacturing?

Why are Americans more productive and richer than Chinese?

As a matter of simple logic, the average income per worker is tied, more or less, to labour productivity, namely the average value-added produced per worker. National income differences boil down to labour productivity differences. (OK, I simplify to clarify. What were you expecting in a Factful Friday?)

Why these differences exist across nations is literally the “holy grail” of economics. And the profession is far from cracking the Da Vinci Code on this one. Economists can tell you how to get farmers to raise more chickens, or how to get people to buy more homes, but there is no reliable formula for pushing the productivity of a country like Mexico up to that of Canada.

In particular, I want to probe whether it is really true that the US is richer than China because American manufacturing is more productive. The corollary question is: Is it really true that the acquisition of advanced manufacturing will help China get rich before it gets old? If that were true, one could understand the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) obsession with manufacturing.

If you’re in a hurry, the nutshell version (with the shell removed) is this: America is not richer because of its manufacturing; too few people work in factories for that to be even remotely plausible.

Touchstone facts.

· The US average value-added per worker in 2019 (the last year before Covid messed up lots of statistics) was $125,283 in current dollars.

· The figure for China was 15% of that: $18,358 to be precise according to the OECD database I’m using (Trade in Employment, 2023 ed).

The Chinese number is lower than the US number because Chinese workers are less productive than US workers. But the productivity gap is not 85% in all sectors. Moreover, the distribution of workers across sectors is quite different in the two nations.

The next set of charts uses these differences to allocate the aggregate, $125,283 versus $18,358, gap across sectors.

Where do workers work?

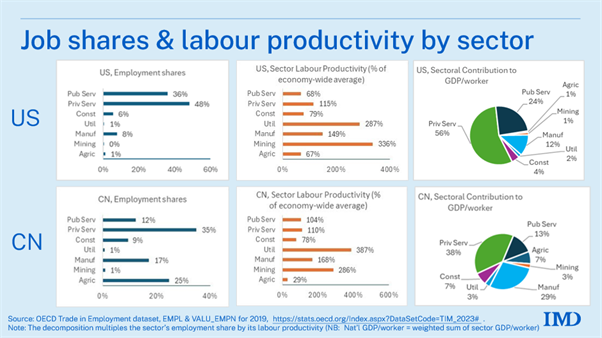

The leftmost charts below show the sectoral employment shares for the US and China.

· About 85% of Americans work in service sectors, while the number is only 47% for China.

· About 17% of Chinese work in manufacturing compared to only 8% for the US.

About a quarter of Chinese still work in agriculture, while US farm workers are rarer than a blue moon on a Tuesday.

How productive are workers who work in the various sectors?

The middle charts show the distribution of labour productivity focusing on sector deviations from the national average. For example, labour productivity in US manufacturing (GDP per worker) is about 50% higher than the US-wide average labour productivity (and that average is, not coincidentally, $125,283 per worker). In China, the manufacturing sector labour productivity is about 170% higher than the Chinese average.

Psst. If I can pull you into a sidebar over here, my brave reader, I’d like to point out a couple of other facts in these middle charts that you might not have known (I didn’t). The most productive sectors are utilities and mining in both nations. Utility workers are about twice as productive as manufacturing workers. There are good reasons for that, but stark, little-known facts are a great way of sparking up a conversation at parties, or at least the ones I go to.

Sectoral contributions to economy-wide GDP per worker.

With the magic of maths, we can combine these two sets of facts into a decomposition of the national productivity (rightmost charts). That is, we can determine how important each sector is in explaining the aggregate productivity numbers ($125,283 for the US and $18,358 for China).[i] Combining the productivity of sectors with the share of workers in the sectors, the rightmost charts tell us which sectors matter most in determining national incomes.

· In the US, about 80% of the national average productivity/income comes from economic activity in the public and private services sectors.

Note that ‘public’ in this context comprises “Public administration, education, health, and other personal services.” Private services are all the rest. The public/private categories are standardised across nations by the OECD, so in some countries, like the US, the “public” services are provided by private firms. (Aren’t you glad you didn’t have to sit in those meetings!)

· In China, the corresponding figure for services is only 51%.

This mostly reflects the greater importance of service jobs in the US. The point being that the service-sector versus average productivity gap isn’t very different in the US and China (68% and 115% for public and private in the US versus 104% and 110% for China).

· For manufacturing, the contribution is 12% for the US and 29% for China.

The much higher contribution of manufacturing in China is due to its much larger employment share (17% versus 8%) and a somewhat higher sector-average productivity gap (149% versus 168%).

What is the takeaway?

· US workers are more productive than Chinese workers due, mostly (80%), to what goes on in the US service sector, not what goes on in the US manufacturing sector (12%).

With these facts in hand, I’d like to turn to a bit of pontification.

Where does mainstream manufacturing mesmerisation come from?

I’m not exactly sure why politicians believe manufacturing is so pivotal for economic success. I get it that you need a manufacturing sector to conduct military operations, react to pandemics, and drive the green transition. I also get it that productivity growth is faster in manufacturing in the G7 nations. But with only 8% of the US workforce having a factory job that is subject to this faster productivity advancement, why isn’t manufacturing more of a “that’s nice to have” sort of thing rather than something Biden threw $2 trillion at? The obsession doesn’t make sense unless it is coming from politics … oh, wait, yes that’s it. Now I get it. Manufacturing jobs win elections. It’s like farm policy in France; no one wins without the farm vote.

While that conclusion is surely part of the truth, it is not the whole truth; especially not in China.

History of thought: Services as faux frais and imaginary output.

In China the shunning of services is easier to comprehend. Communist economic theory is all about production, and from Marx onwards that meant things that you could drop on your foot. Agriculture and mining counted, but the future lay with manufacturing. Marx, a German sitting in London, hatched his masterpiece, Das Kapital, in 1867 when industry was what Germany wanted and England had. It was clearly what gave Britain its superpower status. Karl, of course, wasn’t shilling for the German state. He was writing to make a better life for workers across the world.

Remember, Marxism was not just the whole class-struggle and rising up of the proletariat thing. It also had a plan for economic betterment. That plan relied on industrialising like England did. Manufacturing mesmerisation made sense. The early Marxists didn’t care for services.

· Did you know that Engels called services ‘faux frais’ (false costs)?

I’d read that somewhere many years ago and today popped it into Chatty who explained: Engels used the term to describe ancillary expenses that support the primary production activities.

· Did you know that in the 1990s, the CCP called some service sectors the “imaginary economy” or “fictitious economy” (xūnǐ jīngjì)?

Recall that real socialists don’t believe in market prices. Above all, they don’t believe that market prices represent value. And since, even today, it is hard to evaluate services without just claiming that they are worth what people pay for them, it is easy to understand how a hard-charging communist boss would build factories rather than improve productivity of the service sector.

But this history-of-thought peccadillo could pose problems as it did for the USSR.

Is China making the Soviet mistake?

In my first book, Towards an Integrated Europe (Baldwin 1994), I had to use USSR-era statistics to work out how poor the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) were at the time. This is where I learned about the anti-services inclination of communist planners.

USSR statisticians didn’t use GDP, they used “Net Material Product (NMP)”, which, as the name suggests, includes only foot-droppables. Services were faux frais. And since they had to measure the output, and didn’t trust market prices, and the labour theory of value was too vague for statistical bureaus, economic performance was often measured in terms of physical quantities, such as tons of steel, bushels of grain, or meters of fabric.

Now you can understand why Soviet planners overinvested in heavy industry. Oversimplifying to make the point, consumer goods and services received less priority because they weighed less. This didn’t end well.

When the Berlin Wall fell and markets took over from planners, we found out that the planners had been putting more resources into heavy industry than people were willing to pay for. At the time, the adjustment was called the L-curve. The share of industry in output and employment dropped and stayed down. China’s industry developed in continuous contact with market forces, so the situation is not the same. We won’t see an L-curve. But there are other ways for the factory fetish to fail.

The Soviet Growth Deterioration

Padma (1986) points out that the USSR fixation with heavy industry and tangible outputs and inputs may well have been partly responsible for the Soviet economic slowdown in the 1980s that was, in turn, partly responsible for the downfall of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Soviet growth relied heavily on the accumulation of tangible capital as the source of economic growth. Capital was a foot-droppable and often heavy to boot. “Technical change,” which was not a foot-droppable, played a limited role in either theory or practice (Padma 1986). What she calls ‘Soviet Growth Retardation’ was due to a declining rate of technical change and diminishing returns to capital accumulation.

Summary and concluding remarks.

The key fact here in this week’s Factful Friday is that the average American labour productivity is higher than average Chinese labour productivity because of things going on in the US services sectors, not the US manufacturing sectors. That should give pause to those with the “more manufacturing mania”.

This brings me to the concluding remarks which usually means pontification, and today is no exception.

· Is China making the Soviet manufacturing mesmerisation mistake?

Is the CCP’s understanding of modern economies (together with the fantastic success of their recent industrial effort) leading them to overemphasise industry and infrastructure? Is their mindset blinding them to the potential of service sector that employs half of Chinese workers?

Those aren’t questions that can be answered by facts, but they do deserve, IMHO, a good long ponder.

In my view, China’s problem isn’t overproduction in manufacturing, it’s underproduction of services. And that’s it for another Factful Friday!

References.

Baldwin, R (1994). Towards an Integrated Europe, CEPR Press, London. https://www.brookings.edu/books/towards-an-integrated-europe/

Baldwin, R (2016), The Great Convergence: Information technology and the new globalisation, Harvard University Press (Chapter 3).

Baldwin, R (2019), The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, robotics, and the future of work, Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, R (2023). Where in the world are manufacturing jobs going? Factful Friday, 22 December 2023, Linkedin, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/where-world-manufacturing-jobs-going-richard-baldwin-x1zbe/

Baldwin, R (2024). “China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise”. VoxEU.org, 17 January 2024. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/china-worlds-sole-manufacturing-superpower-line-sketch-rise

Baldwin, R (2024). India vs China: Trade’s role in their industrialisation, Factful Friday, Linkedin, March 15, 2024.

Desai, Padma (1986). Soviet Growth Retardation, The American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 76, No. 2. pp. 175-180.

Gaiman, N., & Pratchett, T. (1990). Good omens: The nice and accurate prophecies of Agnes Nutter, witch. Gollancz.

Jin, K. (2023). The new China playbook: Beyond socialism and capitalism. Penguin Publishing Group. https://thechinaproject.com/podcast/economist-keyu-jin-on-her-new-book-the-new-china-playbook/

Li, David Daokui (2024). China’s World View, W.W. Norton & Company. https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393292398

Wang, Tao (2023). Making sense of China’s economy. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Making-Sense-of-Chinas-Economy/Wang/p/book/9781032317045

[i] For those of you who like/care about such things, the economy-wide average is expressed as the sum of job-weighted sectoral productivities.

If you look at it on a population basis China is still well behind the USA and nowhere near Japan, Germany or South Korea in terms of world manufacturing. China has roughly 4 times the population of the USA. If the USA has 12% of the worlds manufacturing (first graph) then China needs 48% to catch up on a per capita basis. At 35% China is still quite a long way behind the USA.

Talk of Chinese "overproduction" is simply another way of attacking China and scaring people in the West. If China achieves similar living standards to the West in the next few decades, it's economy will be larger than the entire west and many times the size of the USA. This does not mean western living standards have to drop, just that Chinese living standards rise.

This post is genuinely bizarre. The graph literally shows that mining, utilities and manufacturing have the highest productivities, and then suggests that the US has a high productivity because of the service sector, because this is where most people are employed.

If IT and digital tech are included in services, and they are stripped out, and there were only tiny productivity gains in the services graph, and the wrong-headed argument of this logic would still hold: services productivity could be anaemic, and US productivity growth would still be high, because small, highly productive, real-world sectors are doing the heavy lifting.

As Jean Fourastie showed, a large service sector is the consequence of a highly productive real economy, not the other way around. When food, heat, light, communications, and domestic goods are cheap (the stuff that engineers build which can be measured in atoms, watts, electrons and photons), we can spend the rest of our budgets on the cinema, spa treatments and holidays.

People and politicians have a 'fetish' for manufacturing because that is indisputably what created modern prosperity, because it is where technical progress was most emphatically applied. This was the case in Britain, Western Europe, the US, Japan, China, SK.... and it will be every nation that rises to prosperity (except the micro states).