China and the localization of world manufacturing

By Richard Baldwin, Professor of International Economics, IMD Business School, Lausanne

15 December 2023

Today's “Factful Friday” focuses on two sets of facts. The first looks at various indicators that demonstrate the localization of world manufacturing. The second set of charts make the case that China’s own localisation is leading the global trend.

The globalisation ratio for world manufacturing

The chart on the right shows a variation of the classic export-to-GDP ratio. It represents the global value of exports of manufactured goods as a share of world manufacturing production. It's important to note that production and GDP are not the same; production equals GDP plus all the intermediate goods used in making final products.

As evident from the chart, the ratio significantly increased from 1995 to 2008 and then declined almost as rapidly. By 2020, the latest year for which data is available, the level returned to where it was in 2001.

The chart on the left breaks down total exports into final goods and intermediate goods. This reveals an important fact: the behaviours of final goods and intermediates are nearly identical. This is noteworthy because the trading of intermediates, which are business-to-business (B2B) sales, differs significantly from the trading of final goods, which are business-to-consumer (B2C) sales. B2B sales are largely facilitated by organized global value chains. While there may be other interpretations, the similarity of the two series suggest that it is something on the production side that is driving the localisation rather than something on the distribution side.

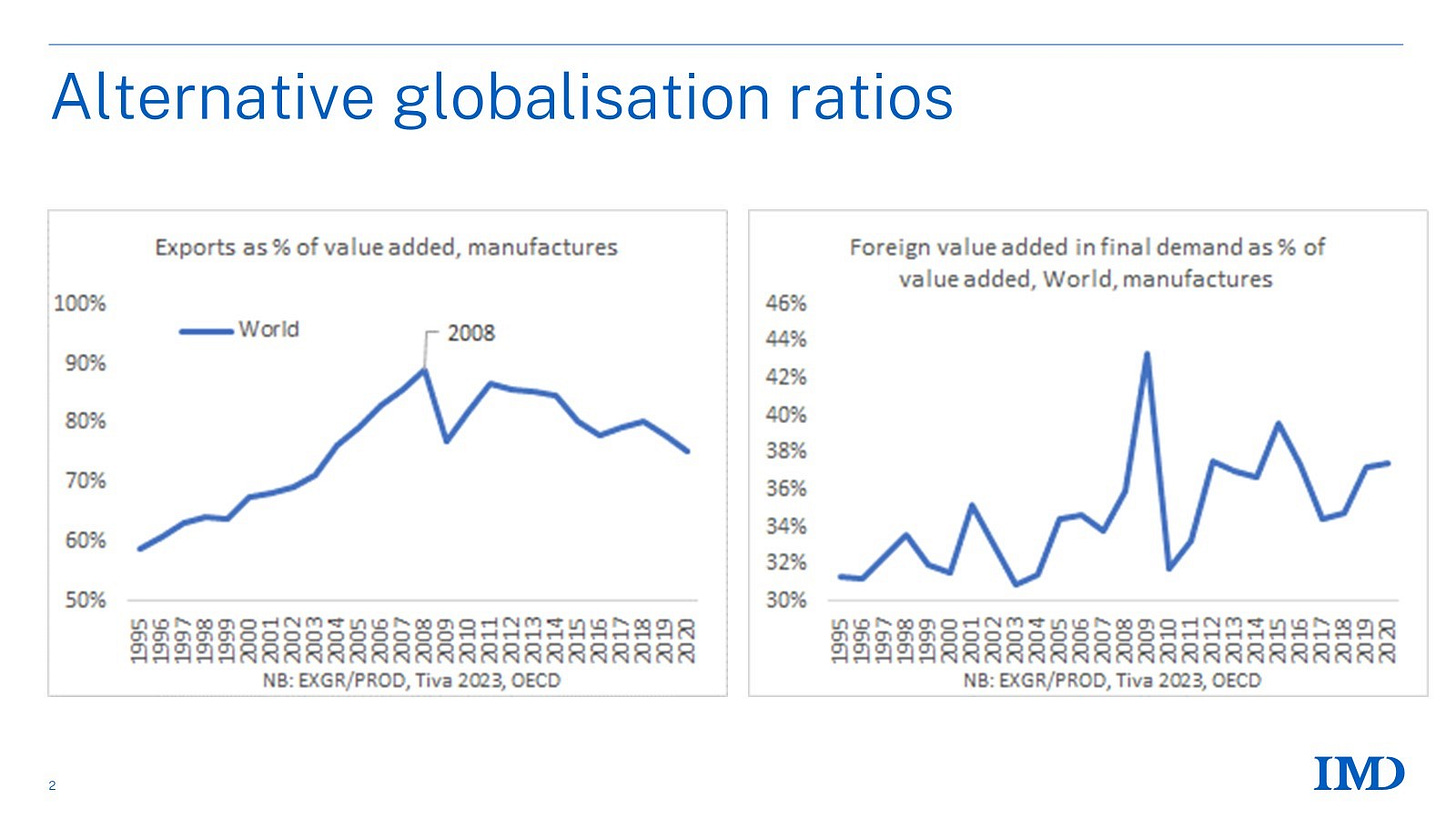

The next pair of charts presents different indicators of the globalization ratio. The left chart shows global manufacturing exports as a share of global manufacturing value added, or GDP. The message is basically identical to the one from the previous charts. Note that while export to GDP is the standard globalisation ratio, it is awkward since the top is in gross terms while the bottom is in value added terms. This is why the ratio for a transshipment nation like Singapore can be over 200%! It is widely used since data on GDP is easier to find than data on gross production.

A slightly more complex version of the globalization ratio is displayed on the right. Here, the numerator represents foreign value added embedded in final demand, while the denominator includes value added in manufacturing. Remember, value added can be calculated either as the sum of inputs or as the value of final outputs. Although this indicator's trend line is more complex than the others, it roughly shows an increase from 1995 to 2009, with most of the peak occurring towards the end, followed by a decline with various fluctuations up to 2020.

To sum up, Fact number one is that:

1. Global manufacturing has been localizing for over a decade, following 15 to 20 years of increasing globalization. This trend holds true across several different measures and for both final goods and intermediate goods.

China’s preponderant role

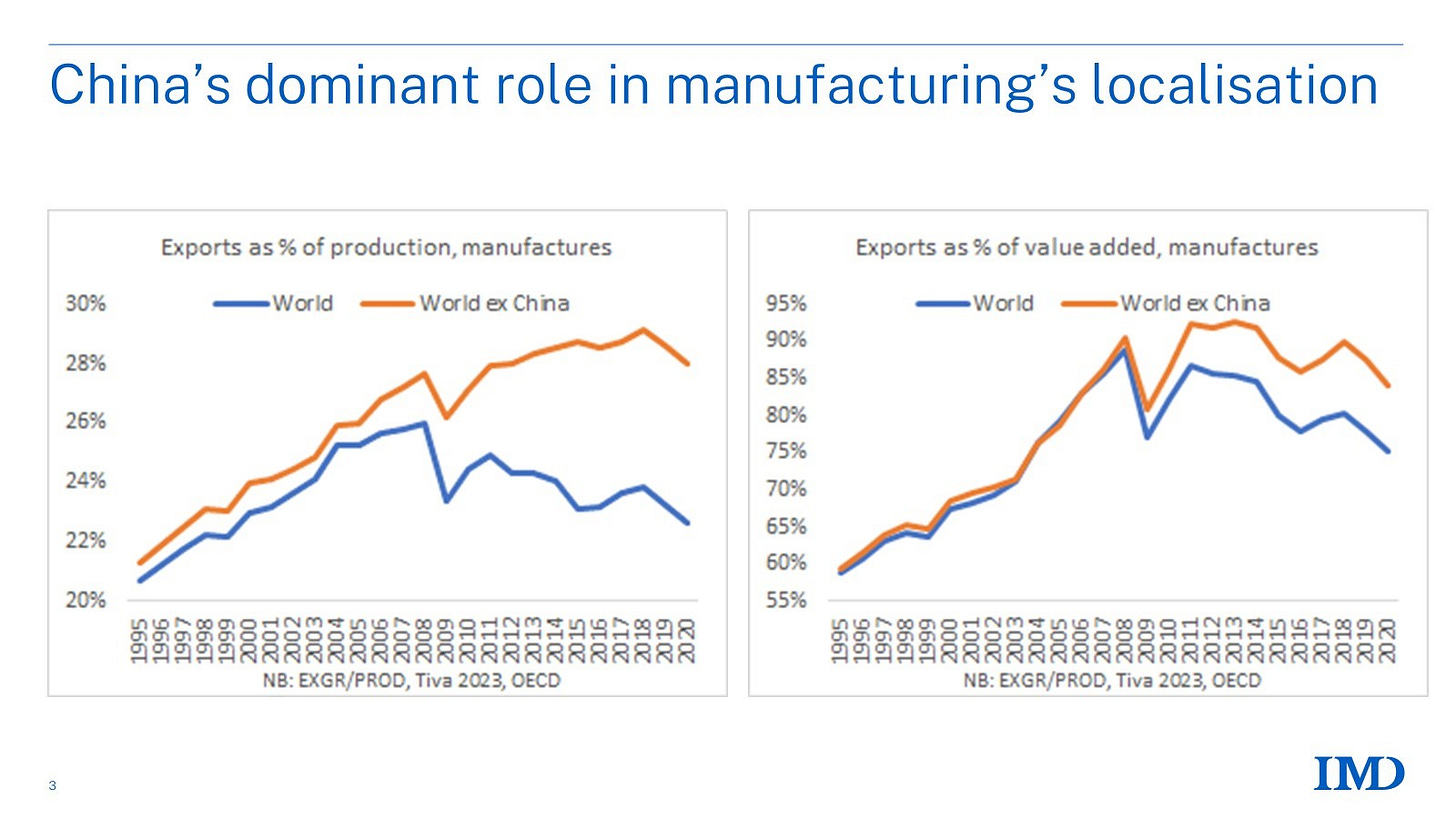

The next pair of charts highlight China's critical role in the global shift towards localized manufacturing over the past 15 years.

The left chart compares the ratio of exports to production for the world overall and the world excluding China. There's a clear divergence observed, with the 'World without China' line continuing to rise, albeit at a slower pace, and experiencing a dip during the COVID years.

On the right, the chart undertakes a similar breakdown, but with exports compared to value added instead of production. Since value added is gross production minus intermediates, the globalization ratio using value added is always higher than that using gross production.

These two measures tell similar stories at a global level but paint quite different pictures when excluding China. Notably, the divergence between the behaviours of the global market and that excluding China is less pronounced. Specifically, the globalization ratio is falling, not just slowing down.

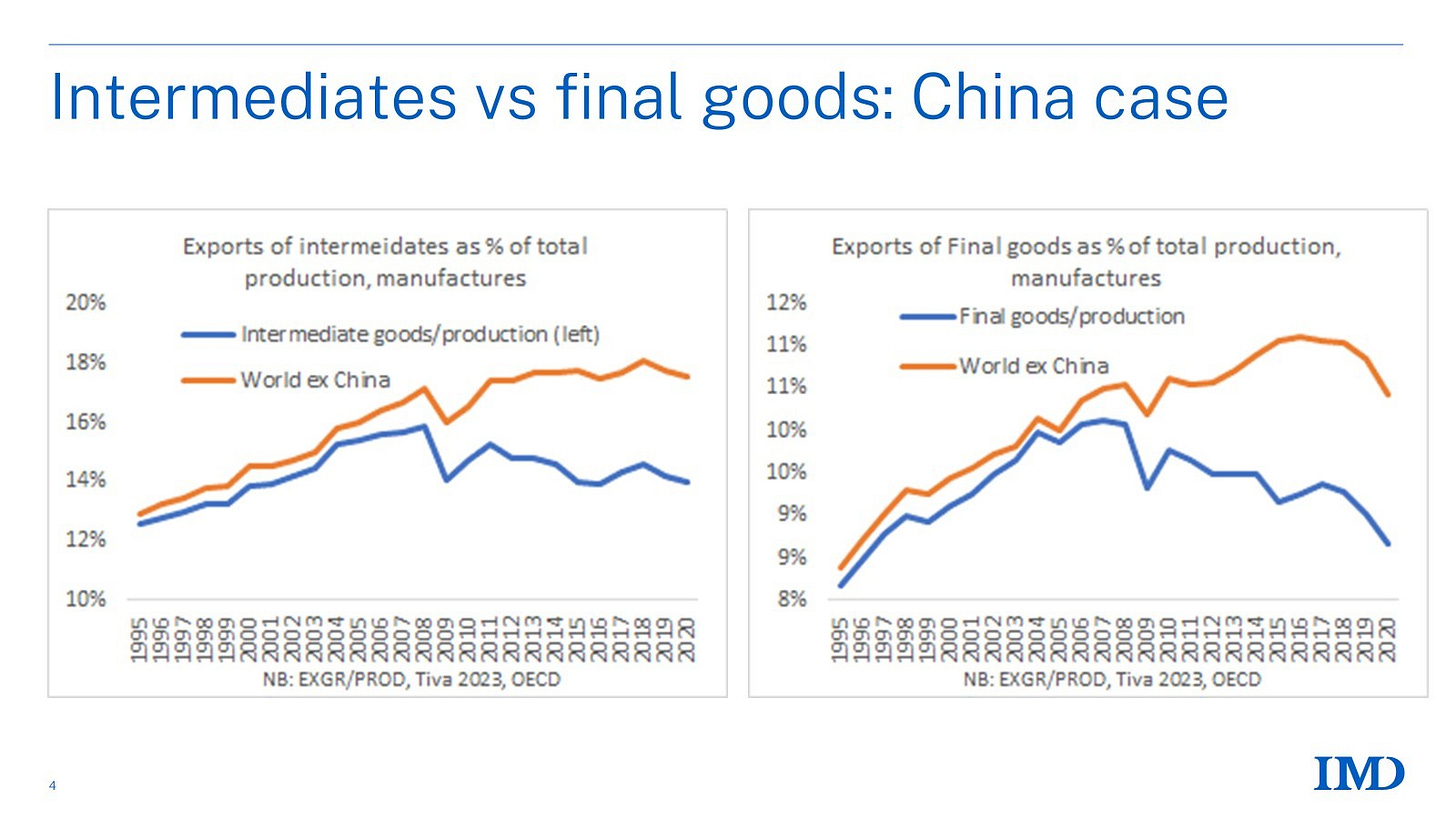

The Next pair of charts return to the split between intermediate and final goods.

Here we see the globalization ratio for intermediates in manufacturing as a share of total manufacturing. Again, the divergence between the series with and without China is evident. However, the globalization ratio for the world excluding China is on a modest upward trajectory. The right chart mirrors this for final goods, with a larger gap noted since China has been increasingly consuming its own final goods. The notable downturn during the COVID years raises questions about whether this is a temporary blip or an emerging trend.

To examine China's impact further, the subsequent pair of charts showcases the remarkable growth of Chinese manufacturing, both in terms of production and value added (left panel).

China's specialization in intermediate goods means its share of global production surpasses its share of value added. This rapid dominance in world manufacturing suggests that the with-and-without-China series are influenced by China's unique characteristics and its significant weight in global figures. The right panel shows China’s globalization ratios with production and GDP in the denominator.

In summary Fact number two is:

1. The global trend towards localizing manufacturing can be largely attributed to China's shift in consuming more of its own manufactured goods. This is evident in both intermediate and final goods, reflecting China's reduced exportation and increased domestic absorption of its production.

BTW, the fact that China’s manufacturing production grows faster than its exports (as it has for many years) is what Jinping Xi is talking about with Dual Circulation.